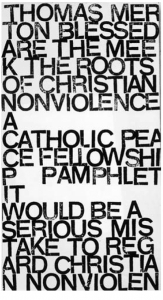

BLESSED ARE THE MEEK:

BLESSED ARE THE MEEK:

The Christian Roots of Non-violence

By Thomas Merton

A Catholic Peace Fellowship Pamphlet Published During the Mid-1960s

It would be a serious mistake to regard Christian nonviolence simply as a novel tactic which is at once efficacious and even edifying, and which enables the sensitive man to participate in the struggles of the world without being dirtied with blood. Nonviolence is not simply a way of proving one’s point and getting what one wants without being involved in behavior that one considers ugly and evil. Nor is it, for that matter, a means which anyone legitimately can make use of according to his fancy for any purpose whatever. To practice nonviolence for a purely selfish or arbitrary end would in fact discredit and distort the truth of nonviolent resistance.

Nonviolence is perhaps the most exacting of all forms of struggle, not only because it demands first of all that one be ready to suffer evil and even face the threat of death without violent retaliation, but because it excludes mere transient self-interest from its considerations. In a very real sense, he who practices nonviolent resistance must commit himself not to the defense of his own interests or even those of a particular group: he must commit himself to the defense of objective truth and right above all of man. His aim is then not simply to “prevail” or to prove that he is right and the adversary wrong, or to make the adversary give in and yield what is demanded of him.

Nor should the nonviolent resister be content to prove to himself that he is virtuous and right, and that his hands and heart are pure enough though the adversary’s may be evil and defiled. Still less should he seek for himself the psychological gratification of upsetting the adversary’s may be evil and defiled. Still less should he seek for himself the psychological gratification of upsetting the adversary’s conscience and perhaps driving him to an act of bad faith and refusal of the truth. We know that our unconscious motives may, at times, make our nonviolence a form of moral aggression and even a subtle provocation designed (without awareness) to bring out the evil we hope to find in the adversary, and thus to justify ourselves in our own eyes and in the eyes of “decent people.” Wherever there is a high moral ideal there is an attendant risk of pharisaism, and nonviolence is no exception. The basis of pharisaism is division: on one had this morally or socially privileged self and the elite to which it belongs. On the other hand, the “others,” the wicked, the unenlightened, whoever they may be, Communists, capitalists, colonialists, traitors, international Jewry, racists, etc.

Christian nonviolence is not built on a presupposed division, but on the basic unity of man. It is not out of the conversion of the wicked to the good ideas of the good, but for the healing and reconciliation of man with himself, man the person and man the human family.

The nonviolent resister is not fighting simply for “his” truth or for “his” pure conscience, or for the right that is on “his side.” On the contrary, both his strength and his weakness come from the fact that he is fighting for the truth, common to him and to the adversary, the right that is objective and universal. He is fighting for everybody.

For this very reason, as Gandhi saw, the fully consistent practice of nonviolence demands a solid metaphysical and religious basis both in being and in God. This comes before subjective good intentions and sincerity. For the Hindu this metaphysical basis was provided by the Vedantist doctrine of Atman, the true transcendent Self which alone is absolutely real, and before which the empirical self of the individual must be effaced in the faithful practice of dharma. For the Christian, the basis of nonviolence is the Gospel message of salvation for all men and of the Kingdom of God to which all are summoned. The disciple of Christ, he who has heard the good news, the announcement of the Lord’s coming and of His victory, and is aware of the definitive establishment of the Kingdom, proves his faith by the gift of his whole self ot the Lord in order that all may enter the Kingdom. This Christian discipleship entails a certy way of acting, a politeia, a conservation, which is proper to the Kingdom.

The great historical event, the coming of the Kingdom, is made clear and is “realized” in proportion as Christians themselves live the life of the Kingdom in the circumstances of their own place and time. The saving grace of God in the Lord Jesus is proclaimed to man existentially in the love, the openness, the simplicity, the humility and the self-sacrifice of Christians. By their example, of a truly Christian understanding of the world, expressed in living and active application of the Christian faith to the human problems of their own time, Christians manifest the love of Christ for men (John 13:35, 17:21), and by that fact make him visibly present in the world. The religious basis of Christian nonviolence is then faith in Christ the Redeemer and obedience to his demand to love and manifest himself in us by a certain manner of acting in the world and in relation to other men. This obedience enables us to live as true citizens of the Kingdom, in which the divine mercy, the grace, favor and redeeming love of God are active in our lives. Then the Holy Spirit will indeed “rest upon us” and act in us, not for our own good alone but for God and his Kingdom. And if the Spirit dwells in us and works in us, our lives will be continuous and progressive conversion and transformation in which we also, in some measure, help to transform others and allow ourselves to be transformed by and with others in Christ.

The chief place in which this new mode of life is set forth in detail is the Sermon on the Mount. At the very beginning of this great inaugural discourse, the Lord numbers the beatitudes, which are the theological foundation of Christian nonviolence: Blessed are the poor in spirit…blessed are the meek (Matthew 5:3-4).

This does not mean “blessed are they who are endowed with a tranquil temperament, who are not easily moved to anger, who are always quiet and obedient, who do not naturally resist.” Still less does it mean “blessed are they who passively submit to unjust oppression.” On the contrary, we know what the “poor in spirit” are those of whom the prophets spoke, those who in the last days will be the “humble of the earth,” that is to say the oppressed who have no human weapons to rely on and who nevertheless are true commandments of Yahweh, and who hear the voice that tells them: “Seek justice, seek humility, perhaps you will find shelter on the day of the Lord’s wrath” (Sophonias 2:3). In other words they seek justice in the power of truth and of God, not by the power of man. Note that Christian meekness, which is essential to true nonviolence, has this eschatological quality about it. It refrains from self-assertion and from violent aggression because it sees all things in the light of the great judgement. Hence it does not struggle and fight merely for this or that ephemeral gain. It struggles for the truth that the right which alone will stand in that day when all is to be tried by fire (I Corinthians 3:10-15).

Furthermore, Christian nonviolence and meekness imply a particular understanding of the power of human poverty and powerlessness when they are united with the invisible strength of Christ. The Beatitudes indeed convey a profound existential understanding of the dynamic of the Kingdom of God – a dynamic made clear in the parables of the mustard seed and of the yeast. This dynamism of patient and secret growth, in belief that out of the smallest, weakest, and most insignificant seed the greatest tree will come. This is not merely a matter of blind and arbitrary faith. The early history of the Church, the record of the apostles and martyrs remains to testify to this inherent and mysterious dynamism of the ecclesial “event” in the world of history and time. Christian nonviolence is rooted in this consciousness and this faith.

This aspect of Christian nonviolence is extremely important and it gives us the key to a proper understanding of the meekness which accepts being “without strength” (gewatlos) not out of masochism, quietism, defeatism or false passivity, but trusting in the strength of the Lord of truth. Indeed, we repeat, Christian nonviolence is nothing if not first of all a formal profession of faith in the Gospel message that the Kingdom has been established and that the Lord of truth is indeed risen and reigning over his Kingdom.

Faith of course tells us that we live in a time of eschatological struggle, facing a fierce combat which marshals all the forces of evil and darkness against the still-invisible truth, yet this combat is already decided by the victory of Christ over death and over sin. The Christian can renounce the protection of violence and risk being humble, therefore, vulnerable, not because he trust in the supposed efficacy of a gentle and persuasive tactic that will disarm hatred and tame cruelty, but because he believes that the hidden power of the Gospel is demanding to be manifested in and through his own poor person. Hence in perfect obedience to the Gospel, he effaces himself and his own interests and even risks his life in order to testify not simply to “the truth” in a sweeping, idealistic and purely platonic sense, but to the truth that is incarnate in a concrete human situation, involving living persons whose rights are denied and whose lives are threatened.

Here it must be remarked that a holy zeal for the cause of humanity in the abstract may sometimes be mere lovelessness and indifference for concrete and living human beings. When we appeal to the highest and most noble ideals, we are most easily tempted to hate and condemn those who, so we believe, are standing in the way of their realization.

Christian nonviolence does not encourage or excuse hatred of a special class, nation or social group. It is not merely anti-this or that. In other words, the evangelical realism which is demanded of the Christian should make it impossible for him to generalize about “the wicked” against whom he takes up moral arms in a struggle for righteousness. He will not let himself be persuaded that the adversary is totally wicked and can therefore never be reasonable or well-intentioned, and hence need to be listened to. This attitude, which defeats the very purpose of nonviolence-openness, communication, dialogue often accounts for the fact that some acts of civil disobedience merely antagonize the adversary without making him willing to communicate in any way whatever, except with bullets or missiles. Thomas à Becket, in Eliot’s play, Murder in the Cathedral, debated with himself, fearing that he might be seeking martyrdom merely in order to demonstrate his own righteousness and the King’s injustice: “This is the greatest treason, to do the right thing for the wrong reason.”

Now all these principles are fine and they accord with our Christian faith. But once we view the principles in light of our current facts, a practical difficulty confronts us. If the “gospel is preached to the poor,” if the Christian message is essentially a message of hope and redemption for the poor, the oppressed, the underprivileged and those who have no power humanly speaking, how are we to reconcile ourselves to the fact that Christians belong for the most part to the rich and powerful nations of the earth. Seventeen percent of the world’s population control eighty percent of the world’s wealth, and most of these seventeen percent are supposedly Christian. Admittedly those Christians who are interested in nonviolence are not ordinarily the wealthy ones. Nevertheless, like it or not, they share in the power and privilege of the most wealthy and mighty society the world has ever known. Even with the best subjective intentions in the world, how can they avoid a certain ambiguity in preaching nonviolence? Is this not a mystification?

We must remember Marx’s accusation that “the social principles of Christianity encourage dullness, lack of self-respect, submissiveness, self-abasement, in short all the characteristics of the proletariat.” We must frankly face the possibility that the nonviolence of European or American preaching Christian meekness may conceivably be adulterated by bourgeois feelings and by an unconscious desire to preserve the status quo against violent upheaval.

On the other hand, Marx’s view of Christianity is obviously tendentious and distorted. A real understanding of Christian nonviolence (backed up by the evidence of history in the Apostolic Age) shows not only that it is a power, but that it remains perhaps the only really effective way of transforming man and human society. After nearly fifty years of Communist revolution, we find little evidence that the world is improved by violence. Let us however seriously consider at least the conditions for relative honesty in the practice of Christian nonviolence.

- Nonviolence must be aimed above all at the transformation of the present state of the

world, and it must therefore be free from all occult, unconscious connivance with an unjust use of power. This poses enormous problems – for if nonviolence is too political it becomes drawn into the power struggle and identified with one side or another in that struggle, while if it is totally apolitical it runs the risk of being ineffective or at best merely symbolic.

- The nonviolent resistance of the Christian who belongs to one of the powerful nations

and who is himself in some sense a privileged member of world society will have to be clearly not for himself but for others, that is for the poor and underprivileged. (Obviously in the case of Negroes in the United States, though they may be citizens of a privileged nation, their case is different. They are clearly entitled to wage a nonviolent struggle for their, rights but even for them this struggle should be primarily for truth itself – this being the source of their power.)

- In the case of nonviolent struggle for peace – the threat of nuclear war abolishes all

privileges. Under the bomb there is not much distinction between rich and poor. In fact the richest nations are usually the most threatened. Nonviolence must simply avoid the ambiguity of an unclear and confusing protest that hardens the warmakers in their self-righteous blindness. This means in fact that in this case above all nonviolence must avoid a facile and fanatical self-righteousness, and refrain from being satisfied with dramatic self-justifying gestures.

- Perhaps the most insidious temptation to be avoided is one which is characteristic of

the power structure itself: fetishism of immediate visible results. Modern society understands “possibilities” and “results” in terms of a superficial and quantitative idea of efficacy. One of the missions of Christian nonviolence is to restore a different standard of practical judgment in social conflicts. This means that the Christian humility of nonviolent action must establish itself in the minds and memories of modern man not only as conceivable and possible, but as a desirable alternative to what he now considers the only realistic possibility: namely political technique backed by force. Here the human dignity of nonviolence must manifest itself clearly in terms of a freedom and a nobility which are able to resist political manipulation and brute force and show them up as arbitrary, barbarous and irrational. This will not be easy. The temptation to get publicity and quick results by spectacular tricks or by forms of protest that are merely odd and provocative but whose human meaning is not clear may defeat this purpose.

- The realism of nonviolence must be made evident by humility and self-restraint which

clearly show frankness and open-mindedness and invite the adversary to serious and reasonable discussion.

Instead of trying to use the adversary as leverage for one’s own effort to realize an ideal, nonviolence seeks only to enter into a dialogue with him in order to attain, together with him, the common good of man. Nonviolence must be realistic and concrete. Like ordinary political action, it is no more than the “art of the possible.” But precisely the advantage of nonviolence is that it has a more Christian and more humane notion of what is possible. Where the powerful believe that only power is efficacious, the nonviolent resister is persuaded of the superior efficacy of love, openness, peaceful negotiation and above all of truth. For power can guarantee the interests of some men but it can never foster the good of man. Power always protects the good of some at the expense of all the others. Only love can attain and preserve the good of all. Any claim to build the security of all on force is a manifest imposture.

It is here that genuine humility is of the greatest importance. Such humility, united with true Christian courage (because it is based on trust in God and not in one’s own ingenuity and tenacity), is itself a way of communicating the message that one is interested only in truth and in the genuine rights of others. Conversely, our authentic interest in the common good above all will help us to be humble, and to distrust our own hidden drive to self-assertion.

- Christian nonviolence, therefore, is convinced that the manner in which the conflict for truth is waged will itself manifest or obscure the truth. To fight for truth by dishonest, violent, inhuman, or unreasonable means would simply betray the truth one is trying to vindicate. The absolute refusal of evil or suspect means is a necessary element in the witness of nonviolence.

As Pope Paul said before the United Nations Assembly in 1965, “Men cannot be brothers if they are not humble. No matter how justified it may appear, pride provokes tensions and struggles for prestige, domination, colonialism and egoism. In a word pride shatters brotherhood.” He went on to say that the attempts to establish peace on the basis of violence were in fact a manifestation of human pride. “If you wish to be brothers, let the weapons fall from your hands. You cannot love with offensive weapons in your hands.”

- A test of our sincerity in the practice of nonviolence is this: are we willing to learn something from the adversary? If a new truth is made known to us by him or through him, will we accept it? Are we willing to admit that he is not totally inhumane, wrong, unreasonable, cruel, etc.? This is important. If he sees that we are completely incapable of listening to him with an open mind, our nonviolence will have nothing to say to him except that we distrust him and seek to outwit him. Our readiness to see some good in him and to agree with some of his ideas (though tactically this might look like a weakness on our part), actually gives us power: the power of sincerity and of truth. On the other hand, if we are obviously unwilling to accept any truth that we have not first discovered and declared ourselves, we show by that very fact that we are interested not in the truth so much as in “being right.” Since the adversary is presumably interested in being right also, and in proving himself right by what he considers the superior argument of force, we end up where we started. Nonviolence has great power, provided that it really witnesses to truth and not just to self-righteousness.

The dread of being open to the ideas of others generally comes from our hidden insecurity about our own convictions. We fear that we may be “converted” – or perverted – by a pernicious doctrine. On the other hand, if we are mature and objective in our open-mindedness, we may find that viewing things from a basically different perspective – that of our adversary – we discover our own truth in a new light and are able to understand our own ideal more realistically.

Our willingness to take an alternative approach to a problem will perhaps relax the obsessive fixation of the adversary on his view, which he believes is the only reasonable possibility and which he is determined to impose on everyone else by coercion.

It is refusal of alternatives – a compulsive state of mind which one might call the “ultimate complex” – which makes wars in order to force reality. The mission of Christian humility in social life is not merely to edify, but to keep minds open to many alternatives. The rigidity of a certain type of Christian thought has seriously impaired this capacity, which nonviolence must recover.

Needless to say, Christian humility must not be confused with a mere desire to win approval and to find reassurance by conciliating others superficially.

- Christian hope and Christian humility are inseparable. The quality of nonviolence is decided largely by the purity of the Christian hope behind it. In its insistence on certain human values, the Second Vatican Council, following Pacem in Terris, displayed a basically optimistic trust in man himself. Not that there is not wickedness in the world, but today trust in God cannot be completely divorced from a certain trust in man. The Christian knows that there are radically sound possibilities in every man, and he believes that love and grace always have the power to bring out those possibilities at the most unexpected moments. Therefore if he has hopes that God will grant peace to the world it is because he also trusts that man, God’s creature, is not basically evil: that there is in man a potentiality for peace and order which can be realized provided the right conditions are there. The Christian will do his part in creating these conditions by preferring love and trust to hate and suspiciousness. Obviously, once again, this “hope in man” must not be naïve. But experience itself has shown, in the last few years, how much an attitude of simplicity and openness can do to break down barriers of suspicion that had divided men for centuries.

It is therefore very important to understand that Christian humility implies not only a certain wise reserve in regard to one’s own judgments – a good sense which sees that we are not always necessarily infallible in our ideas – but it also cherishes positive and trustful expectations of others. A supposed “humility” which is simply depressed about itself and about the world is usually a false humility. This negative, self-pitying “humility” may cling desperately to dark and apocalyptic expectations, and refuse to let go of them. It is secretly convinced that only tragedy and evil can possibly come from our present world situation. This secret conviction cannot be kept hidden. It will manifest itself in our attitudes, in our social action and in our protest. It will show that in fact we despair of reasonable dialogue with anyone. It will show that we expect only the worst. Our action seeks only to block or frustrate the adversary in some way. A protest that from the start declares itself to be in despair is hardly likely to have valuable results. At best it provides an outlet for the personal frustrations of the one protesting. It enables him to articulate his despair in public. This is not the function of Christian nonviolence. This pseudo-prophetic desperation has nothing to do with the beatitudes, even the third. No blessedness has been promised to those who are merely sorry for themselves.

In resume, the meekness and humility which Christ extolled in the Sermon on the Mount and which are the basis of true Christian nonviolence are inseparable from an eschatological Christian hope which is completely open to the presence of God in the world and therefore in the presence of our brother who is always seen, no matter who he may be, in the perspectives of the Kingdom. Despair is not permitted to the meek, the humble, the afflicted, the ones famished for justice, the merciful, the clean of heart and the peacemakers. All the beatitudes “hope against hope,” “bear everything, believe everything, hope for everything, endure everything.” (I Corinthians 13:7). The beatitudes are simply aspects of love. They refuse to despair of the world and abandon it to a supposedly evil fate which it has brought upon itself. Instead, like Christ himself, the Christian takes upon his own shoulders the yoke of the Savior, meek and humble of heart. This yoke is the burden of the world’s sins with all its confusions and all its problems. These sins, confusions and problems are our very own. We do not disown them.

Christian nonviolence derives its hope from the promise of Christ: “Fear not, little flock, for the Father has prepared for you a Kingdom.” (Luke 12:32)

The hope of the Christian must be, like the hope of a child, pure and full of trust. The child is totally available in the present because he has relatively little to remember, his experience of evil is as yet brief, and his anticipation of the future does not extend far. The Christian, in his humility and faith, must be as totally available to his brother, to his world, in the present, as the child is. But he cannot see the world with childlike innocence and simplicity unless his memory is cleared of past evils by forgiveness, and his anticipation of the future is hopefully free of craft and calculation. For this reason, the humility of Christian nonviolence is at once patient and uncalculating. The chief difference between nonviolence and violence is that the latter depends entirely on its own calculations. The former depends entirely on God and on His word.

At the same time the violent or coercive approach to the solution of human problems considers man in general, in the abstract, and according to various notions about the laws that govern his nature. In other words, it is concerned with man as subject to necessity, and it seeks out the points at which his nature is consistently vulnerable in order to coerce him physically or psychologically. Nonviolence on the other hand is based on that respect for the human person without which there is no deep and genuine Christianity. It is concerned with an appeal to the liberty and intelligence of the person insofar as he is able to transcend nature and natural necessity. Instead of forcing a decision upon him from the outside, it invites him to arrive freely at a decision of his own, in dialogue and cooperation, and in the presence of that truth which Christian nonviolence brings into full view by its sacrificial witness. The key to nonviolence is the willingness of the nonviolent resister to suffer a certain amount of accidental evil in order to bring about a change of mind in the oppressor and awaken him to personal openness and to dialogue. A nonviolent protest that merely seeks to gain publicity and to show up the oppressor for what he is, without opening his eyes to new values, can be said to be in large part a failure. At the same time, a nonviolence which does not rise to the level of the personal, and remains confined to the consideration of nature and natural necessity, may perhaps make a deal but it cannot really make sense.

It is understandable that the Second Vatican Council, which placed such strong emphasis on the dignity of the human person and the freedom of the individual conscience, should also have strongly approved “those who renounce the use of violence in the vindication of their rights and who resort to methods of defense which are otherwise available to weaker parties too.” (Constitution on the Church in the Modern World, n. 78) In such a confrontation between conflicting parties, on the level of personality, intelligence and freedom, instead of with massive weapons or with trickery and deceit, a fully human solution becomes possible. Conflict will never be abolished but a new way of solving it can become habitual. Man can then act according to the dignity of that adulthood which he is now said to have reached – and which yet remains, perhaps to be conclusively proved. One of the ways in which it can, without doubt, be proved is precisely this: man’s ability to settle conflicts by reason and arbitration instead of by slaughter and destruction.

The distinction suggested here, between two types of thought – one oriented to nature and necessity, the other to persona and freedom – calls for further study at another time. It seems to be helpful. The “nature-oriented” mind treats other human beings as objects to be manipulated in order to control the course of events and make the future for the whole human species conform to certain rather rigidly determined expectations. “Person-oriented” thinking does not lay down these draconian demands, does not seek so much to control as to respond, and to awaken response. It is not set on determining anyone or anything, and does not insistently demand that persons and events correspond to our own abstract ideal. All it seeks is the openness of free exchange in which reason and love have freedom of action. In such a situation the future will take care of itself. This is the truly Christian outlook. Needless to say that many otherwise serious and sincere Christians are unfortunately dominated by this “nature-thinking” which is basically legalistic and technical. They never rise to the level of authentic interpersonal relationships outside their own intimate circle. For them, even today, the idea of building peace on a foundation of war and coercion is not incongruous – it seems perfectly reasonable.Ω

*Note: This pamphlet was also reprinted in Volume 8.1 of the CPF Journal: The Sign of Peace. You can find a link that entire issue on “Thomas Merton, peacemaker” below: